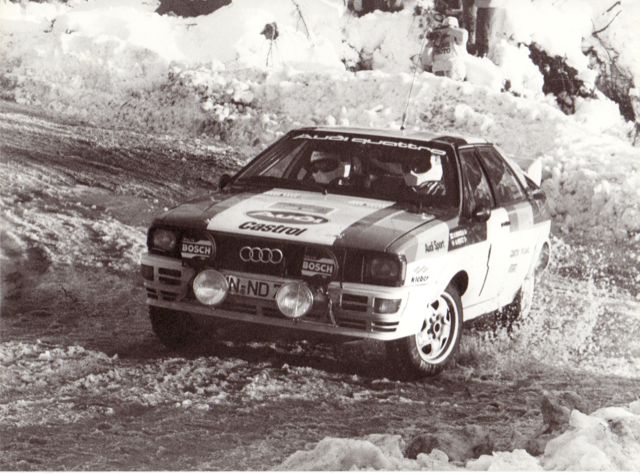

Today would have been Hannu Mikkola’s 82nd birthday. What better way to remember and celebrate the 1983 world champion than to go back in time to when he got a telephone call from what was then West Germany? It was 1979. Did he want to come to Ingolstadt? He was fascinated by what he heard. Eero Wihuri tells the story, Carita Keinänen and Girardo & Co provide the pictures.

You will never forget that sight. A darkening evening along a central Finland gravel road, the rain splashing, the feeling of waiting. And soon the silence will end with bangs coming from the exhaust. The five-cylinder turbocharged engine offers more than 500bhp, skillfully administered by Finnish rally legend Hannu Mikkola.

The car moves incredibly fast. Sharp braking, turning into the bend and accelerating away. The exhaust flame flashes into the air. On the roadside, viewers are amazed by what they’ve just seen. Each of them on the last weekend of August 1985 on the 1000 Lakes Rally will remember the Audi Sport Quattro E2 driven by Hannu Mikkola and Swedish team-mate Stig Blomqvist. The big-winged Audi became an icon of Group B. It has been described as the most brash, brutal, and wild rally car.

But how did the story of Audi Quattro start? How did the development go from the first four-wheel drive turbocharged Quattro to the big-winged Audi in a few years?

This incident on the 1985 1000 Lakes was the precursor to an astonishing and record-breaking drive through Ouninpoja

It’s early summer 2019 on sunny Kuusisaari, a Helsinki island. Hannu Mikkola sits on the couch in his living room, with Seurasaari Bay in the background. He tells the story of the Quattro, while fellow rallying great Simo Lampinen listens. Mikkola saw and experienced the entire Audi rally journey from 1979 to 1987, when the manufacturer stopped competing in the WRC.

Phone call from West Germany

Hannu Mikkola’s career made a new turn in 1979. Mikkola, who had been driving a rear-wheel-drive Ford Escort in the WRC, got a phone call from Germany. He was asked to come to the Audi factory in Ingolstadt, a city of over 120,000 people on the Danube in Bavaria, back then West Germany. Mikkola decided to go see what Audi wanted to show him.

“In Ingolstadt, I was waiting for a four-wheel-drive, turbocharged Audi Quattro,” he recalled. “It was a civilian car that I could drive. The car was a big secret – it was only introduced the following year at the Geneva Motor Show. When I tried the Quattro, Audi representatives told me that the factory had decided to go to the WRC. They asked me to develop the car and then compete with it.”

Mikkola drove the car on small roads near the factory.

“I didn’t get a perfect picture of what kind of car the Quattro was. But something fascinated me. I started to think that I would be a fool if I didn’t get involved. I was afraid of missing the next phase of development, so I accepted Audi’s offer.

“I signed a two-year contract, starting with testing in 1980. At first, Audi believed that it could start competing as early as 1980, but I told them that testing would take the whole year.”

The early Quattro had around 300bhp, but the only way was up from there

Audi was also interested in the services of German star driver Walter Röhrl. However, he was not interested in the contract offer.

“Walter didn’t dare come to Audi,” said Mikkola. “Later, when the car had been developed through 1980, I showed him the times I had driven at the Algarve Rally as zero car. Still after that, Walter didn’t dare to enter the project. He did not come to Audi until 1984, when everything was ready.”

Audi’s arrival into rallying with a four-wheel drive car was primed in the late 1970s. Mikkola explained: “Audi and Volkswagen conducted winter tests in Lapland, northern Finland. Audi engineer Jörg Bensinger tested the Volkswagen Iltis military SUV and noticed that on slippery terrain, its four-wheel drive was faster than any other car. The Iltis was faster than the big Audi, even though the Audi had a lot more power. From this realization, Audi decided to develop the four-wheel drive Quattro.

“In the spring of 1980, Audi’s sporting department conducted the development of the Quattro under the general direction of Ferdinand Piëch. The car was badly unfinished, and due to insufficient technology, the combination of four-wheel drive and handling was difficult. In the beginning, the car was practically three-wheel drive!

“In early summer 1980, we had a test on the outskirts of Athens after the Acropolis Rally. We drove the special stages used in the rally and compared times. Piëch wanted to come to follow the tests – as a technology guy, he was interested in the development of the car.”

It was there that Piëch realized the car needed more work.

“During the tests, a list of over 20 issues was created,” Mikkola recalled. “Piëch wanted me to report him directly on the progress of the development work. Communication started and Piëch always answered my phone calls.

“After that, the development of the rally car was accelerated. Audi brought four-wheel drive and turbocharged engines to rallying. The technology got developed through many mistakes.

“The biggest problem at first was the turbo lag. It did not provide power with the gas pedal movement, but instead with a delay, at worst in the middle of the next corner. It then gave so much power that it straightened the car. Over time, the delay was removed.”

The first rally Quattro boasted around 300bhp, rapidly increasing to over 350. The Sport Quattro and the E2 surpassed over 500bhp. But taming the turbo lag required Mikkola to change his driving technique.

“The power quickly increased,” said Mikkola. “The change was drastic considering the rear-wheel-drive Escort had around 260bhp at its best. Suddenly there was 100bhp more. However, you got used to the power and the four-wheel-drive car didn’t whine like the rear-wheel drive.

In the early 1980s there were no electronics. Mechanical medicines were used.Hannu Mikkola

“I had driven rear-wheel-drive cars with right-foot braking. With the Audi, I started driving with the left-foot braking. While braking with the left, I adjusted the engine revs [with the right] so that the [turbo] delay wouldn’t surprise me.”

Mikkola also expanded on his assertion that initially the car was practically three-wheel drive.

“Only one of the front-end wheels could pull,” he said. “At first, there was no lock [differential] at the front end, there was a solid lock in the middle and a lamellar lock at the back.”

The solution was found in a newspaper story that Mikkola read. His eyes caught a story about Jensen’s four-wheel drive car, with a Ferguson differential and locks.

“The magazine praised the functionality of the system,” Mikkola said. “That gave me the idea that a similar solution could be tried on the Audi as well. A lock was developed at the front end, thanks to which the car did not tend to shoot in every direction, but the power could come on more smoothly.

“You have to remember that in the early 1980s there were no electronics to control the power transmission. Today, adjusting cars is done with the help of computers, but then mechanical medicines were used.

“The year was a bit too short, but in the fall of 1980 we already knew the car was really fast.”

Many outsiders doubted whether the Audi would be able to match lighter, more agile two-wheel drive cars. How wrong they were

Storm warning in Monte

Audi’s competitiveness was widely questioned. Rallying people wondered how a harsh and large ‘SUV’ could do well against agile rear-wheel drive.

“We all thought that Hannu’s career was fading due to the Audi agreement,” admitted Lampinen. “We could not imagine that Audi had developed a revolutionary rally car. We skeptics were proven wrong. The Audi was a great car and Hannu Mikkola played a big role in its development. Hannu was the fastest driver of the WRC for several years and won the World Championship in 1983.”

Audi’s first World Rally was the 1981 Monte Carlo. There, Hannu Mikkola gave a storm warning. In slippery conditions, he recorded fastest time after the fastest time and led the rally by more than eight minutes. Victory only escaped him due to brake failure.

“The brake pipes broke,” Mikkola said. ”The brakes disappeared completely. I turned the front of the car into the mountain wall to slow down, then went out.”

But Mikkola won the next rally in Sweden. The new era had begun. In 1981 and 1982, Mikkola and Audi were the fastest combination of the WRC, but numerous technical issues torpedoed their championship hopes. In 1981, Mikkola won the Swedish and the RAC Rally and was third in the final points.

In 1982, he won the 1000 Lakes and the RAC, and was again third in the standings. But in 1983, Mikkola succeeded in winning the world championship. During the season, he won four WRC events: Sweden, Portugal, Argentina and the 1000 Lakes. In addition, he was second on the Safari, Ivory Coast and RAC.

In 1984, Mikkola slightly lightened his WRC program. He won Rally Portugal and was second in the championship. The following year, Mikkola contested four WRC events, and finished only once, placing fourth on Rally Sweden. At that time, Mikkola also competed in the British Open rally series with the Audi Quattro. His influence allowed David Sutton’s renowned private team to run the Quattro in Britain.

In 1986, the final year of Group B, Mikkola drove the Audi Quattro S1 to third place on the Monte, his only WRC rally of the season. When Group A took over, Audi competed for just under a season with the 200 Quattro in 1987. Mikkola won the Safari with the big ‘tank’ and was third on the Acropolis.

In total, Audi drivers Mikkola, Blomqvist, Röhrl and Michele Mouton achieved 23 WRC rally victories. Blomqvist emulated Mikkola’s drivers’ championship success in 1984, and Audi won the manufacturers’ championship in 1982 and 1984.

Competition tightens

Audi was the only factory team in the WRC with a four-wheel-drive car between 1981 and 1983. Its main competitor, Lancia, whose drivers included Markku Alèn, Walter Röhrl and Henri Toivonen, were competing with the rear–wheel drive 037.

Audi got a truly worthy competitor in 1984 when Peugeot brought the mid-engined, four-wheel drive 205 with Ari Vatanen as its driver.

“The long-wheelbase Quattro evolved from Group 4 to Group B,” recalled Mikkola, “and the A2 Quattro was already quite an improvement. It had a reduced bodyweight with, for example, fiberglass doors, and the engine had also been lightened while producing more power.”

A trio of Finns ready to fly in Finland. (l-r) Hannu Mikkola, Ari Vatanen and Markku Alén in the Rantasipi car park

In the spring of 1984, Audi brought the ‘short Quattro’ or Sport Quattro to the WRC. Compared to the old A1 and A2 models, the wheelbase of the Sport Quattro was shortened by 32cm. The shortening was accomplished by removing a section from behind the front doors. Other noticeable changes to the body were Kevlar fenders, which housed 18-inch rims, compared to 17-inch rims on the original Quattro. The front of the car still had a heavy but efficient five-cylinder turbo engine. It was not ideal in terms of weight distribution, and because of the front weight, it was prone to grounding.

“The Sport Quattro was difficult to drive,” said Mikkola. “The car oversteered and understeered at the same time so it was difficult to drive the corners quickly. On the big jumps on 1000 Lakes Rally 1984, the special chassis solutions led to the front wheels coming out of the wheel housings in an oblique position. The car had a clearly more powerful engine than before, but drivability deteriorated. I myself didn’t have much time to test the Sport Quattro before it came to the rallies because I was busy competing.

“For Audi’s German engineers, the solution to the handling problems was clear: more power was developed for the engine. Increased power made the car even more difficult to drive.”

The Sport Quattro was a failed model so Audi continued to develop an evolution version, the E2, which was given its debut on Rally Argentina in the summer of 1985. Compared to the previous version, the car had significantly larger spoilers and wings that increased the exterior dimensions of the car. The wheelbase remained unchanged, but the track widths were increased.

The rear spoiler especially had great importance. At 120km/h (75mph), it pressed the rear wheels down with a force of more than 500kg. At the same time, the engine was updated and raised power from about 450bhp to well over 500bhp.

“Dieter Basche, engineer at Audi, who was the most skilled engineer I ever met during my rally¬ing career,” said Mikkola. “Dieter designed the big wings on the car, which created the car’s downforce. The wing-Audi was much better to drive.

”We knew that due to weight distribution and thus drivability, a mid-engined car would be better than a car with a heavy five -cylinder engine in the front. However, Audi’s management did not give permission to make a mid-engined car. A prototype was made secretly, and it was driven. Audi’s management was not pleased when the construction of an unauthorized prototype was revealed.”

Mikkola’s best WRC result for the E2 was the third place on the 1986 Monte Carlo Rally.

“It was an incredible car,” he said. “The faster you drove, the more the wings pressed the car on the road surface. It was difficult to distinguish where the grip ended. The car had the performance, but at the same time I found it quite safe. There was no need to sit on the gas tank in the Audi.”

Audi’s swansong

Audi stopped competing in the WRC in 1986. Initially, the team planned to participate in six events but the management decided to withdraw after the fatal accident for Henri Toivonen and Sergio Cresto on Corsica.

“The FIA decided to end the era of Group B at the end of the 1986 after Henri’s accident,” said Mikkola. “Walter Röhrl and I were invited to see the Audi board of directors. Ferdinand Piëch and Wolfgang Happel, CEO of Audi, asked me if Group B cars were dangerous now or only at the end of the year.

”Walter and I honestly replied that the rallies are dangerous at the moment. Piëch informed us of Audi’s withdrawal. He said that he and the board of Audi could not take responsibility if we had an unfortunate accident. Piëch was also interested in transferring Audi’s competition to the track, as it did.”

The Basche-inspired wings helped keep the E2 planted on terra firma... most of the time

Mikkola and Röhrl were given a free hand to compete with other teams for the remaining rallies of 1986 . However, neither of them took up the offer.

“Lancia wanted me to drive the Delta S4 as Markku Alèn’s teammate, which meant I was offered Henri’s vacant seat,” recalled Mikkola. “Lancia’s competition coordinator Ninni Russo was very active, he called me many times. However, I was not enthusiastic about Lancia’s offer.

“I could even have chosen which races I would compete in with Lancia, and ultimately they made a good offer for me just for the 1000 Lakes Rally. However, I refused all Lancia’s offers because I did not want to compete with a car where they sat on top of the petrol tank because it was too dangerous. In addition, adapting to the Lancia would have required a lot of testing.”

However, Audi still returned for the 1987 season with the 200 Quattro. The German manufacturer had two models that fitted into Group A rules: the turbocharged but large 200 Quattro, and the smaller but normally aspirated Coupe Quattro. Based on test runs, Audi selected the 200 Quattro. With that car, Mikkola achieved his last WRC victory on the Safari Rally.

The Sport Quattro was "difficult to drive" according to Mikkola, who claimed it understeered and oversteered all at once

“At the end of the year, Audi decided to quit rallying and move to the track,” said Mikkola. “This also ended my competition with Audi. I received an offer from Mazda and I switched, with Timo Salonen as my team-mate.”

Audi revolutionized rallying by bringing four–wheel drive and turbocharging. Hannu Mikkola played a big role in the development of the Quattro. He went to Audi as its first driver and he was the last to leave.

Although Hannu Mikkola competed successfully with Ford Escorts for many years, he is best remembered as Mr. Quattro. It is a great legacy for the rallying world.